In honor of Drink Beer Day (yes, that’s a real day according to Daysoftheyear.com), I’ve wanted highlight one intriguing feature of the four Sanborn maps I had found a few weeks ago through Penn State’s Digital Collections. I am still focusing on my hometown of Renovo for my final project, but would like to tie in local businesses that were around during the town’s early years.

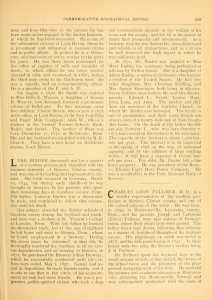

One such local business was Binder’s Brewery, which was owned by the Binder family from 1872 until at least 1911 (still need to find complete history). The original owner of Binder’s Brewery, Luke Binder, had emigrated to the United States from Germany with his parents at the age of 8 and settled in Cambria County. Luke attended St. Vincent College in Latrobe, PA and moved to Altoona where he worked at a brewery and married another German immigrant, Maximilliana (Mary) Endris/Endress in 1871. A year later Binder purchased an already established brewery in Renovo and the couple raised their family, who would continue in the family’s business after Binder died in 1897. The image on the right is a page from the Commemorative Biographical Record of Central Pennsylvania, which was published in 1898 by the coincidentally-named publisher, J.H. Beers & Co. This source is the most authoritative one that I have found on Binder, but information found through Findagrave.com has given me further sources to trace on the Binder family. This information about the family is interesting, but I’m not sure how to turn it into a map project about Renovo, unless I map the travels of Binder from Germany to Pennsylvania.

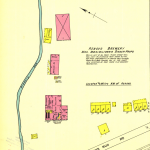

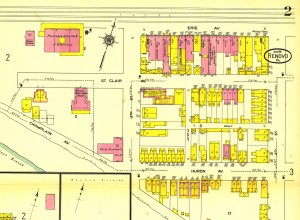

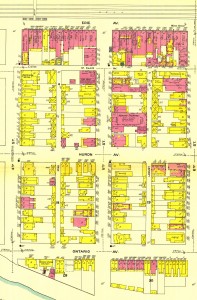

The Sanborn maps above show the changes made to the brewery from 1887 to 1911, including the change in ownership to Mrs. Binder after Luke’s death in 1897 and the change from wood structures to brick. It also shows the geographic location of the brewery, nestled between mountains and a flowing stream, which the brewery used to make their beer. As a kid, our family would often go to Brewery Run to fill up jugs of spring water to drink. I never realized why it was called Brewery Run until recently! I’m not sure if any remains of the brewery are left standing, but I may investigate on my next trip back home. Hopefully I can get more research done on the railroad and other local businesses while I’m there, too.

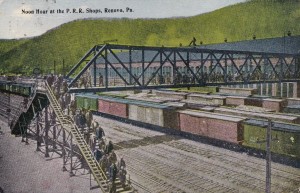

Ideally, I would like to do a project on the distribution of beer from Binder’s Brewery, but I am not sure where those records could be found, or if they even exist. I plan on reaching out to the Clinton County Historical Society to see if they can help point me in the right direction. I would like to see how far the beer traveled and if the brewery utilized the railroad in any fashion. I suspect that they did, but I need to find out how. The location of the brewery is on the western end of the town and not next to a rail line. Perhaps they loaded up horse-drawn carts with barrels and then loaded the freight onto the train? I am not sure how that worked, but I’ve been looking at some books about the history of beer and brewing to see if I can connect the dots.

I feel like I have a lot of ideas at this point and just need to pull them altogether. Right now, I’m focusing mostly on the connection between the brewery and the railroad within the town, but may have to expand my scope a bit depending on what I can dig up. If anyone has any suggestions, I’m all ears!

A few sources I have looked at so far:

This week I’ve commented on Dale’s blog post on his ideas for his final project on Camp Alger.

Last week I commented on Michael’s blog post about his historical atlas evaluation.